The Importance of Archival Description

Margot Note

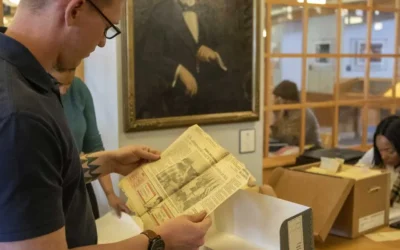

Researchers are demanding greater access to archival collections. At the same time, archives often reduce the level of processing. Can current descriptive standards and developments help solve this dilemma?

An inherent tension exists between providing access and describing archival holdings appropriately.

Finding aids and bibliographic records contain archival description for discovery, management, and understanding. Descriptions detail collection characteristics, content, and purpose. Describing archival materials require archivists to analyze, organize, and note details about the collections, such as creators, titles, dates, extent, and contents.

Although finding aids were created to describe content, they were not created to share information with a wider audience, especially those who use a cataloging database system. Basic archival principles can be brought into bibliographic description in several ways. Archivists recognize the importance of provenance in archival description. They understand that description should be at the group level since most archival material exists at this level. In addition, archival materials are preserved for reasons different from those for which they were created. They also require the flexibility of various levels of description.

Encoded Archival Description

EAD (Encoded Archival Description) was initiated in 1993 through the University of California’s Berkeley Finding Aid project. The goal was to create a standard for describing archives and manuscripts in a machine-readable format. By standardizing description, organizations such as the Research Library Group (RLG) can index the information and allow users to search the collections of repositories across the country.

Developing Encoded Archival Description (EAD) supplied a tool to help mitigate the geographic distribution of collections, which limited the ability of researchers to use primary sources. The goal of EAD is universal intellectual access. Researchers have always urged the off- and online publication of archival holdings to make their work easier. Descriptive coding involves designating what each important component is. Making MARC a description markup system ensured that information could be exploited in multiple ways and made it possible to apply future uses unknown in the early stages of development. The success with MARC AMC, which described at the collection level, made it possible to make finding aids available through EADs.

The development of the format has led archivists to think more systematically about how archival work is conducted. Additionally, archivists realized the benefit of following standards, after a long tradition of using idiosyncratic descriptive practices.

The EAD’s DTD (document type definition) specifies the elements to describe a collection and the arrangement of those elements. DTD’s goals are naming and defining elements, naming and defining attributes, and deciding where and in what sequence elements should appear. The DTD structure could be used for new archival finding aids and existing finding aids. The elements were repeatable to mimic the hierarchical structure of finding aids.

Authority Information

Provenance can be used as a basis of access and retrieval and not just as an underlying concept for arrangement. Provenance information—information about the records creators—can be used as authority information.

Archivists must be able to separate information about records creators from information about the records themselves. There is a benefit to building the authority information into the system instead of having separate authority files, as generally exist in libraries. Again, this makes even more sense in an era when a smaller percentage of an institution’s users come to the repository.

Function plays a role in arrangement and description in terms of access. Functions exist but are not always carried out by the same agency over time. A need exists to track that function, whether the name of the office or its place in the larger organization changes.

The fluidity of function leads to the notion that one series could belong to several records groups over time. Again, there is a hierarchy for the organization but not for the records.

Change and Continuity

Archival description encompasses the dual processes of cataloging and production of finding aids. The complexities of modern organizations and the detachment of description (especially online) from the actual materials have complicated descriptive practices for archivists.

Margot Note

Margot Note, archivist, consultant, and Lucidea Press author is a regular blogger and popular webinar presenter for Lucidea, provider of ArchivEra, archival collections management software for today’s challenges and tomorrow’s opportunities. Read more of Margot’s posts here.

Similar Posts

Collaborative Archival Relationships

Collaborative projects are instrumental in showcasing how archival collections can benefit various organizational departments.

Informational, Evidential, and Intrinsic Values within Archives

Archives provide authentic, reliable information and hold values that reflect their functions and uses; informational, evidential, and intrinsic.

A Sustainable Archives

Archivists prioritize sustainable practices and policies, rooting their work in ethics of care, often preferring digital processing and preservation

Archival Branding and PR Strategies

Archivists who adopt branding and PR strategies both safeguard historical treasures and contribute to their organizations’ evolution.

Leave a Comment

Comments are reviewed and must adhere to our comments policy.

0 Comments