Librarians and Older Technology Part 4: Photographs

Miriam Kahn, MLS, PhD

Photographs are integral components of collections in libraries, archives, museums, historical societies, and even record centers. Including digital images of photographs in finding aids and catalogues increases chance for discovery and use by researchers.

Today, cultural institutions collect or create digital images of photographs for inclusion in databases, catalogs, and online exhibitions. Photographs document the history of individuals, places, and events, shedding light on the past and present.

Historical background

Photography, that is printing using light, was invented in the early 19th century, the most famous inventors being Louis Daguerre, Nicéphore Niépce, and Henry Fox Talbot. Once invented, photographic printing techniques and developing processes proliferated across Europe and the Americas. Numerous inventors, scientists, and artists experimented with photographic processes—each inventor adopting photography to their needs, from documenting microbes to stars, to capturing images of people and historical events.

Common formats

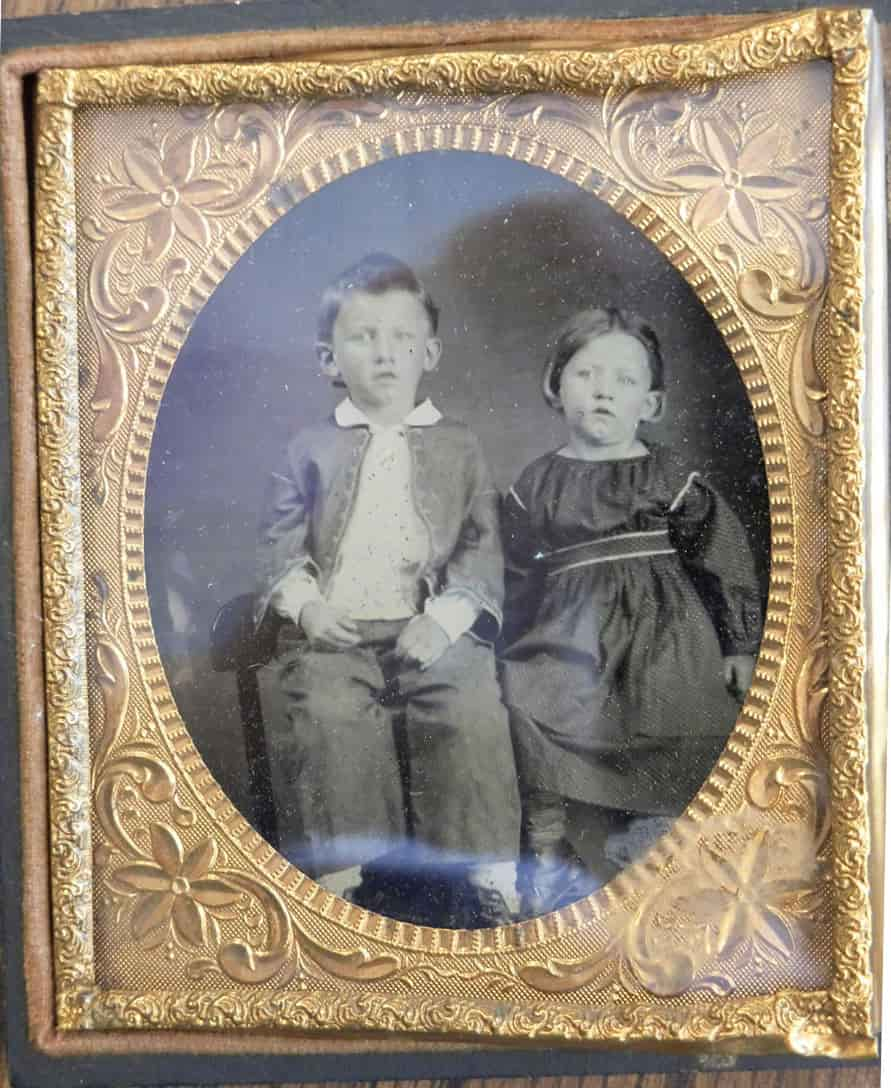

Daguerreotype, ambrotype, and tintype are the most common early photographic formats of the nineteenth century. They were printed on silver-coated glass, red glass, and tin respectively. They are easily recognizable because the photographs were mounted inside cases. Beginning around 1840, photographs captured images of individuals both living and dead, in the rare instance, cityscapes and landscapes.

Tintypes were easily transported and were sometimes mounted into cardboard frames as opposed to cases. The three processes were in common use until the end of the nineteenth century.

The next photographic process, glass plates, were also used throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner both used glass plates to document the Civil War. Glass, both wet and dry plate, negatives were also used to photograph the stars and microscopic objects.

At the same time, photographers were experimenting with printing onto paper and cardstock and printers were using photographs to create images on stones for lithographic printing and subsequent inclusion in newspapers, magazines, and books. Photographic formats include carte de visite (visiting card or calling card) ranging in size from 2”x3” to 6”x8” and larger (beginning in 1854).

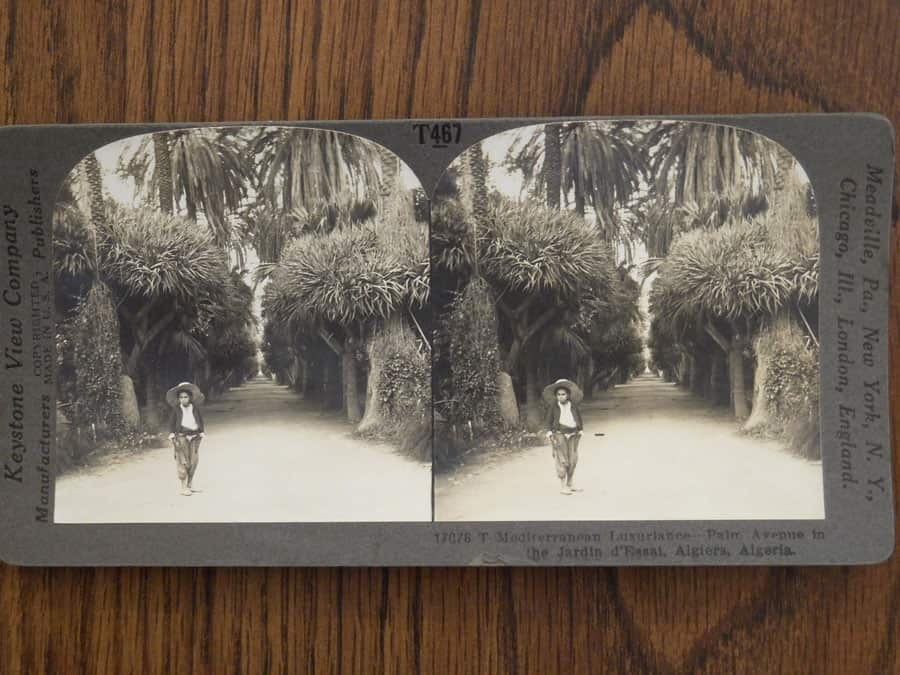

Stereographs, pairs of images that, when seen together, appear 3D. Stereographs were often sold in sets like tourist postcards today and were used for educational purposes. They include images of places and buildings as well as people.

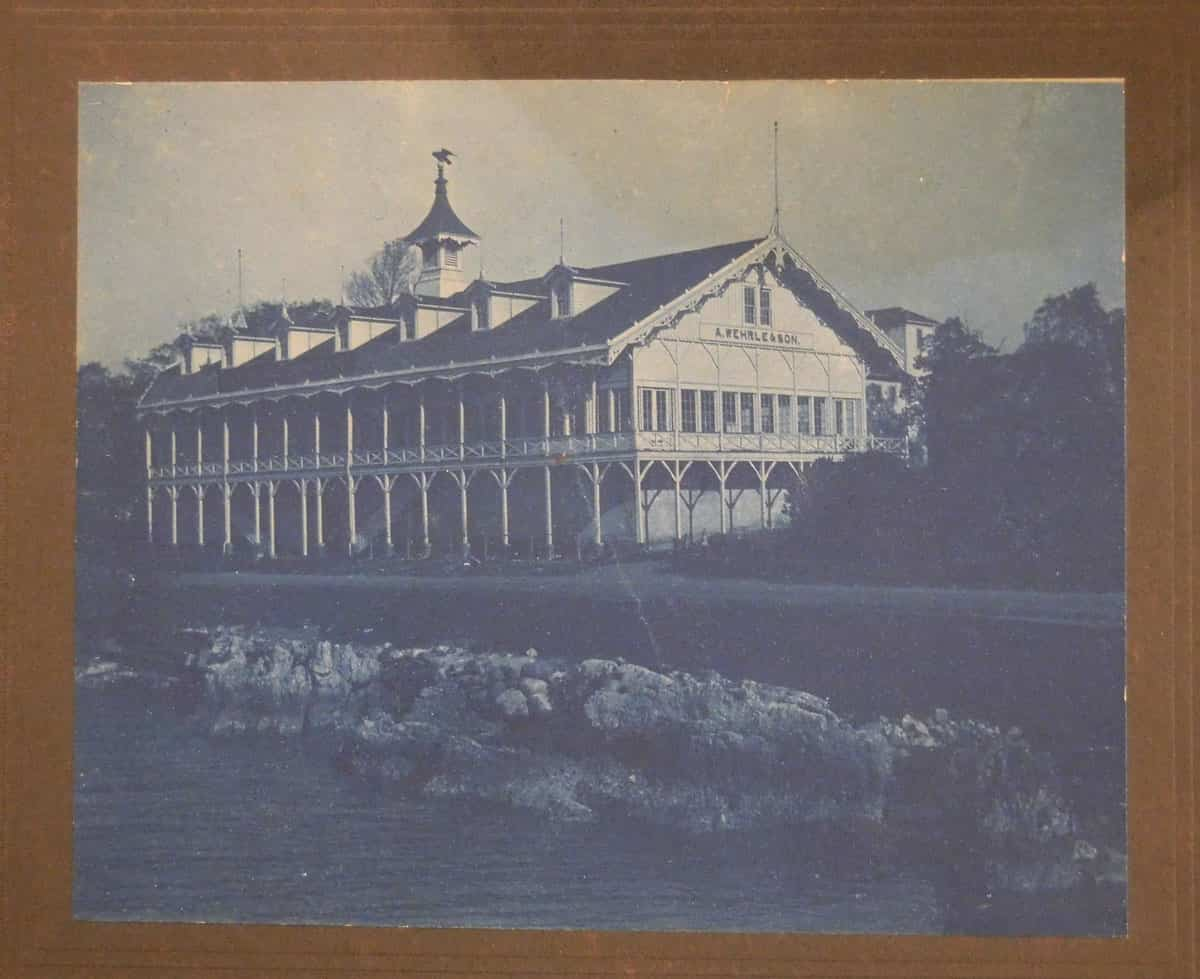

An easily recognizable photographic process is Cyanotype first used in 1842 to print plants and leaves. These are blue and made using the same process as blueprints. They are striking in their blue hues.

A wide range of photographic processes that were printed out from the negative or film base onto paper. The processes range from gelatin and collodion to platinotype. In the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth, you’ll find photogravure and later half-tone and letterpress for printing in newspapers and magazines.

If you have a large collection of photographs, it’s possible you have lantern slides which were used for teaching and lecture collections. These are images on small pieces of glass (3”x 4”) that were used with early slide projectors. Lantern slides have black tape holding the two panes of glass together, are usually labeled, and are stored in wooden boxes.By the early twentieth century, photographs were printed onto paper and cardstock and can be found in numerous sizes. Negatives may or may not be included in your collections. You’ll also find slides that document events, locations, and buildings. Slides are just negative or positive photographs where each frame is mounted in cardboard or plastic.

Cataloging and Description complications

- After locating photographs in your collection, make them available to your researchers. If the photographs are part of series, indicate the overall subject and number of items in the catalog record. Include overall subject terms, natural language tags, and photographer as creator.

- Provide information about the content of the images: people, places, things, and events.

- Identify the process or photograph type, indicate availability for research, and attach a representative sample of images.

- Use the Scope & Content field in finding aids to describe photographs in archival collections.

- Add information about the availability of the physical photographs along with selected images in the catalog or database record if the photographs are supplemental or additional volumes in a monographic series or publication.

- Unidentified photographs can be dated by dress and accessories, inventions and visible technology (wagons, carriages, and cars), and buildings in the cityscape.

Composition, Storage, and Handling

Most photographs and negatives are composed of three layers: base (which can be glass, silver or tin), paper, and in the case of negatives, glass, nitrate, acetate, and now polyester. The image is embedded in the emulsion—that’s the outermost layer of chemicals—and adhered to the base using a binder of Albumen, Gelatin or Collodion. There are one- and two-layer photographs but they are less common.

Handle photographs and negatives by the edges only and / or while wearing lint-free cotton gloves.

Photographs and negatives should be used in a normal library environment. They do require long-term storages at cooler or even freezing temperatures to increase their longevity. Warm to room temperature before use.

Color photographs fade over time. The dyes shift and deteriorate. To preservation color photographs and negatives, store them in appropriate photograph containers away from the light. Silver-based or coated photographs, particularly daguerreotypes, will tarnish when exposed to light and heat. Store them away in appropriate storage containers.

Preservation recommendations for long-term storage of photographs are:

- 60-68 degrees Fahrenheit with a relative humidity 35-55% for regularly used photographs.

- Long term storage of black and white images 45-60 degrees Fahrenheit with a relative humidity of 35-55%. Allow time for the photographs and negatives to warm up before using, one day for every ten degrees below 68.

- Color photographs can be stored at 32 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Nitrate negatives should be isolated from all other negatives, and stored below 32 degrees Fahrenheit. If in good condition, images on nitrate film should be reproduced on safety film or as digital images and the originals stored away or disposed of according to federal hazardous materials standards.

Photograph storage areas should be away from ozone generating equipment, particularly photocopiers. The areas should be dust free if possible, to avoid damage to the emulsion. Store photographs with their identifying information or accession numbers and house like processes and sizes together.

Summing it up

Photographs are commonly found in archival, historical, and museum collections and less commonly in record centers. Make photographs accessible to researchers by providing as much identifying information as possible in the catalog or database record, including time period, subject headings, natural language tags, development or printing process, and relation to series or collection. Store in a dark, environmentally stable conditions and handle with lint-free gloves to avoid damaging the emulsion layer.

Further reading:

Graphic Atlas – for identification of formats of photographs and negatives http://www.graphicsatlas.org/

Image Permanence Institute – for publications and guideline about film, photographs, and negatives https://www.imagepermanenceinstitute.org/

Gernsheim, Helmut. A Concise History of Photography. NY: Dover Publications, Inc., 1986.

Lavédrine, Bertrand. Photographs of the Past: Process and Preservation. (Los Angeles, CA: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2009.

Reilly, James M. Care and Identification of 19th Century Photographic Prints. Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak, 1985, fourth printing (2009).

Ritzenthaler, Mary Lynn and Diane Vogt-O’Connor. Photographs: Archival Care and Management. Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2006.

Severa, Joan. Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans & Fashion, 1840-1900. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1995.

Victoria & Albert (V&A) Museum “Photographic Processes” https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/photographic-processes

Wilhelm, Henry. The Permanence and Care of Color Photographs: Traditional and Digital Color Prints, Color Negatives, Slides, and Motion Pictures. Grinnell, IA: Preservation Publishing Company, 1993. Downloadable at http://wilhelm-research.com/book_toc.html

Miriam Kahn, MLS, PhD

Miriam B. Kahn, MLS, PhD provides education and consulting for libraries, archives, corporations, and individuals. See Miriam’s pieces for Lucidea covering library technology and skills for special librarians. Also check out SydneyEnterprise, and GeniePlus, Lucidea’s powerful integrated library systems.

Similar Posts

How to Incorporate Interns in Museum CMS Projects: Data Cleanup and Refinement

A museum expert details how interns can be successfully included in museum CMS projects at the data cleanup and refinement stage.

Interview with Susannah Barnes about the SLA Data Community

Susannah Barnes is the Co-Lead of the Data Community for the Special Libraries Association. If you work with data in any capacity, this interview will be of interest to you.

Enhancing Collaboration; Methods for Archivists

Archivists can enhance collaboration through user-centric approaches and efficient processing methods based on customer service principles.

Lucidea’s Lens: Knowledge Management Thought Leaders Part 67 – Shawn Callahan

KM Thought Leader Shawn Callahan helps analytically-minded executives tell stories that ultimately inspire action from employees and customers.

Hosting service

Enjoy all of the benefits of your Lucidea solution with secure, reliable, stress free hosting

Programs & incentives

No matter your size or budget, we’ve got you covered, today and tomorrow

Leave a Comment

Comments are reviewed and must adhere to our comments policy.

0 Comments