Redaction in Archives: Ethical Imperatives in a Digital-First World

Margot Note

Redaction in archival work—obscuring or removing sensitive information from records—has become a central concern in contemporary archival ethics. As archives increasingly acquire born-digital records and digitize historical collections for online access, archivists must grapple with data privacy, access, transparency, and potential harm.

While redaction has long been used in government and legal records, its role in archival practice is evolving in ways that reflect broader shifts in how archivists view their moral responsibilities to the public and the individuals represented in their collections.

The Purpose of Redaction in Archives

Traditionally, redaction is used to prevent disclosing confidential, classified, or sensitive information. In archival settings, this might include Social Security numbers, medical diagnoses, sexual orientation, political affiliations, or the names of individuals who could face harm if identified. For instance, a court transcript may reveal addresses, or oral history recordings may identify vulnerable community members.

Redaction serves a dual purpose: it protects individuals while preserving the integrity of the remaining document for research and historical understanding.

However, redaction is not neutral. Institutional priorities, legal frameworks, social values, and practical constraints shape decisions about what to obscure and leave visible. These decisions raise ethical questions about censorship, transparency, and the potential erasure of marginalized voices or uncomfortable truths. As archives move into the digital era, these ethical tensions become even more pressing.

Digital Challenges

Digital archives have complicated the redaction process. In the analog era, redacting a document often meant using a black marker or covering sensitive information before photocopying. Today, redaction requires sophisticated tools to ensure sensitive data is visually hidden and removed from the underlying file. Failure to do so can result in data breaches, even when information is redacted on the surface.

Digital records also create new vulnerabilities. Metadata, email headers, file histories, and other hidden elements can reveal more than intended. As a result, digital redaction in archives must be thorough and technically sound, yet even the best tools cannot make ethical judgments. That responsibility falls to archivists.

Archivists must evaluate the risk of harm by certain disclosures, considering context, content, and audience. This approach requires technological proficiency and ethical clarity. When, for example, should the name of a whistleblower be redacted from a government report? Should the diary of a historical figure be altered if it includes disparaging or offensive language about others? These are complex questions, and there are rarely simple answers.

Redaction as Harm Reduction

One ethical framework gaining traction in archival work is harm reduction. Borrowed from public health and social services, this approach emphasizes minimizing the potential harm of disclosure rather than aiming for perfect safety or unrestricted openness.

Applied to archives, harm reduction reframes redaction as an ethical practice of care rather than simply a technical procedure. Harm reduction acknowledges that all archival work risks exposure, retraumatization, or misuse and calls for thoughtful strategies to mitigate it.

In the context of redaction, harm reduction might involve obscuring only the most sensitive details, such as personal addresses or identifying information about minors, while maintaining as much of the original record as possible. It may also mean collaborating with affected communities to determine what they consider harmful or invasive. Especially in community archives, redaction is increasingly seen as a tool of consent, care, and institutional risk management.

Balancing Redaction with Transparency

The ethical use of redaction also requires a commitment to transparency. Archivists should document when redactions have been made, explain their rationale, and indicate the categories of information that were removed when possible. This approach allows users to understand the context of the record and assess its reliability.

Transparency helps prevent redaction from becoming a means of erasure. In the past, institutions have redacted or withheld records to protect their reputations or to avoid difficult conversations about racism, violence, or exploitation. Today’s archivists must be vigilant against these misuses. Redaction should serve the interests of the individuals in the records, not shield institutions from accountability.

Clear policies, donor agreements, and access guidelines are essential. When redaction is conducted according to consistent, ethical standards, it strengthens public trust in archives. It shows that archivists take the right to know and be protected seriously.

The Path Forward

As redaction becomes more central to archival practice, archivists must continue to refine their ethical frameworks. Professional guidelines from organizations such as the Society of American Archivists provide foundational principles, but each institution must adapt those principles to its specific context, user community, and collections.

Training in digital redaction tools, ethical reasoning, and privacy law is increasingly necessary for archival professionals. Equally important is fostering a culture of reflection, collaboration, and accountability. Archivists must be willing to question their assumptions, learn from affected communities, and revise practices as new challenges emerge.

When done thoughtfully, redaction can protect individuals, preserve the integrity of collections, and support the archives’ role as a site of justice and truth. In an age of digital abundance and vulnerability, archivists must use redaction as a scalpel wielded with care, precision, humility, and moral responsibility.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the difference between redaction and restriction?

Redaction removes or obscures information within a record, while restriction limits access to the entire record. Both processes protect sensitive data in archives, but redaction allows broader access while safeguarding privacy.

What tools are used for digital redaction?

Archivists use specialized software that permanently removes hidden data such as metadata, file histories, and annotations. Common tools include Adobe Acrobat Pro and open-source alternatives, though training and verification are crucial.

How do archives decide what to redact?

Decisions around redaction in archives are guided by a mix of legal requirements, ethical frameworks, donor agreements, and institutional policies. Increasingly, archivists also consult affected communities to determine what information could cause harm.

Margot Note

Margot Note, archivist, consultant, and Lucidea Press author, is a frequent blogger and popular webinar presenter for Lucidea—provider of ArchivEra, archival collections management software for today’s challenges and tomorrow’s opportunities. Download a free copy of Margot’s latest book, The Archivists’ Advantage: Choosing the Right Collections Management System, and explore more of her content here.

Never miss another post. Subscribe today!

Similar Posts

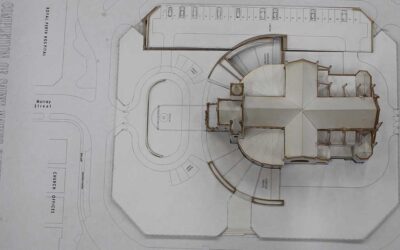

Cultivating a Community of Archival Practice: A Client’s Success Story

“We need a dynamic system that supports a consistent approach to managing the Perth diocesan collections across Western Australia…ArchivEra is already providing this with Catholic dioceses in Bendigo, Hobart, and Ballarat.”

Honoring Cultural Protocols in Archival Practice

Learn how archives can honor Indigenous cultural protocols, reframe stewardship, and move toward ethical, reciprocal, and community-driven practices.

Centering Sovereignty in Archives: Decolonial Approaches to Indigenous Knowledge

Margot Note explores how centering sovereignty in archives supports Indigenous rights, decolonial practice, justice, and cultural resurgence.

The Ethical Use of Born-Digital Materials in Archives

Born-digital records introduce complex ethical dilemmas involving consent, privacy, preservation, and access. Archivists must rethink ethical frameworks to navigate digital records’ dynamic, fragmented, and often personal nature.

Leave a Comment

Comments are reviewed and must adhere to our comments policy.

0 Comments