KM Component 14 – Knowledge Capture Process

Stan Garfield

Knowledge capture includes collecting documents, presentations, spreadsheets, records, processes, software source code, images, audio, video, and other files that can be used for innovation, reuse, and learning.

Gartner defines knowledge capture as “one of the five activities of the knowledge management process framework. Knowledge capture makes tacit knowledge explicit, i.e., it turns knowledge that is resident in the mind of the individual into an explicit representation available to the enterprise.”

Dave Snowden asserts, “If you ask (people) to give you your knowledge on the basis that you may need it in the future, then you will never receive it.” This suggests that it is difficult to capture knowledge. And even if you do capture it, there is no guarantee that it will be reused.

Many KM programs emphasize capture too much – collecting lots of documents, but not being able to effectively reuse them. It is reasonable to question the value of devoting significant energy to document collection in advance of a need.

Taking these caveats into consideration, it is nonetheless useful to establish processes for capturing knowledge for later reuse. As long as you don’t get carried away with attempting to capture all documents, a capture process can be helpful in providing a supply of reusable content. There is still value in capturing some information in easily retrievable repositories.

An example of a capture process is storing information on every project undertaken by an organization in a project repository. This allows members of the organization to search the database to find out if there is knowledge from previous projects which can be applied to new ones.

This can be used in multiple ways. Sometimes you need to answer the question “have you ever done this before” when proposing a new project to a customer. Or you want to review lessons learned from prior work. Reusing documents such as proposals, statements of work, project plans, and designs is another benefit of knowledge capture.

Not all of the documents created by previous projects may have been captured, but if the names of the project team members are available, then it is possible to contact them to request other relevant documents. And it can be helpful to discuss their experiences, insights, and suggestions before embarking on similar efforts.

A project repository can have a fairly simple entry form for information about the project. It might include the project name, a unique identifier, customer, industry, country, solution, a brief description of the project, and a list of the team members. This may be all the information that is required, with the option to associate other documents that are project related.

Another example is a white paper capture process for tips, rules of thumb, insights, or nuggets of knowledge. These can be categorized by the type of subject, and people can subscribe to and read the white papers based on their interests. If someone has solved a particular problem or has come up with a concept which they think other people might benefit from knowing, a capture process for easily publishing their knowledge can lead to sharing and reuse.

Without such a process, it’s possible that those who are known for their good ideas may be repeatedly contacted by others seeking the benefit of their experience and expertise. After the fifth or sixth time of explaining the same information over and over again, those being contacted will appreciate a way for them to capture that information so that it is in one place that everybody can access.

Collection and Supply

Capturing explicit knowledge requires collection processes and repositories, which involve attempting to codify and encapsulate knowledge in writing or some other form of stored data. Explicit knowledge is formal knowledge that can be conveyed from one person to another in systematic ways. Examples include books, documents, white papers, databases, policy manuals, email messages, spreadsheets, methodologies, multimedia, and other types of files.

Collection provides the supply side of knowledge. There must be a supply of knowledge in order for it to be reused. Supply-side knowledge management includes collecting documents and files, capturing information and work products, and storing these forms of explicit knowledge in repositories. Tacit knowledge can also be captured and converted to explicit knowledge by recording conversations and presentations, writing down what people do and say, and collecting stories.

Examples of supply include project databases, skills inventories, and document repositories. The content which is captured represents the raw materials. These can then be analyzed, codified, disseminated, queried, searched for, retrieved, and reused.

Even if every possible document and knowledge object is captured and stored, there is no resultant benefit unless there is significant reuse of all that content. Be sure to keep supply and demand approaches in balance.

Case Study: Knowledge Capture at HP

One of the three goals in the HP Engagement Knowledge Management program was capture, which meant capturing the content and experience from customer bids and projects. This included such things as project summaries, lessons learned, proven practices, white papers, bid documents, and project deliverables.

The formal goal was: Capture content and experience from all customer bids and projects (project profiles, lessons learned reports, bid/project documents, solution collateral/service kit content, knowledge briefs). It was measured by the number of new project profiles in the Project Profile Repository, divided by the number of new projects.

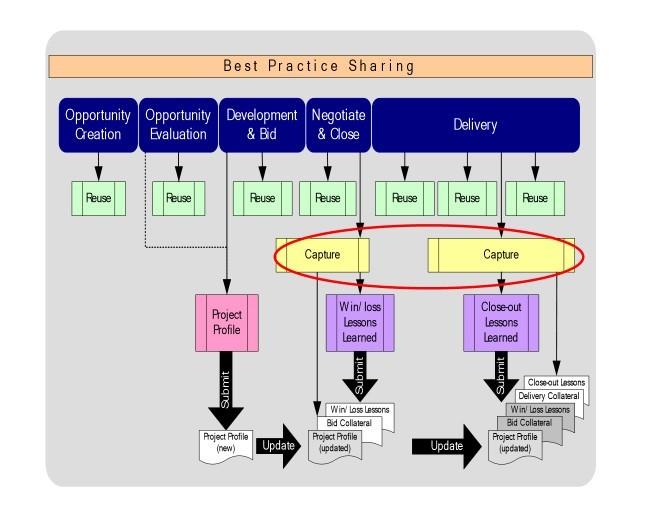

To help achieve the goal, HP embedded knowledge capture into the customer engagement process. The HP Customer Engagement Road Map was the process required to be followed from opportunity creation to delivery. It was the basis of the Engagement Knowledge Map on the HP Knowledge Network homepage. It displayed a grid of steps and resources necessary to carry out a client engagement.

Across the top of the grid were five categories: opportunity creation, opportunity evaluation, development and bid, negotiate and close, and delivery. People followed the roadmap because it was integrated into the process.

Knowledge Capture & Reuse (KCR) was an official process and policy which specified when knowledge is to be captured and reused. Project Startup included the required submission of a Project Profile to the Project Profile Repository (PPR). The Project Closeout process included a requirement to capture project lessons learned.

Initially, there was a problem with capturing project profiles. The quality of the information submitted was often poor, with missing or inaccurate data. HP assigned the people who supported the knowledge help desk an additional task: review all project profile submissions and approve only those that met a minimum quality test. Submissions that failed this test were followed up to ensure good data. HP measured and reported on the quality, and after a year, the quality was nearly 100% and the process was working perfectly.

Stan Garfield

Please enjoy Stan’s additional blog posts offering advice and insights drawn from many years as a KM practitioner. You may also want to download a copy of his book, Proven Practices for Implementing a Knowledge Management Program, from Lucidea Press. And learn about Lucidea’s Inmagic Presto and SydneyEnterprise with KM capabilities to support successful knowledge curation and sharing

Similar Posts

Only You Can Prevent Knowledge Loss: How to Practice “Knowledge Archaeology”

An overview of ways in which knowledge is lost, with examples of how to perform knowledge archaeology to recover and restore it.

Ready to Read: Profiles in Knowledge: 120 Thought Leaders in Knowledge Management

We are pleased to announce that Stan Garfield’s new book, Profiles in Knowledge: 120 Thought Leaders in Knowledge Management, is now available from Lucidea Press.

Lucidea’s Lens: Knowledge Management Thought Leaders Part 92 – Jay Liebowitz

Jay Liebowitz is a professor, consultant, author, and editor. His research interests include knowledge management, data analytics, intelligent systems, intuition-based decision making, IT management, expert systems, and artificial intelligence.

Lucidea’s Lens: Knowledge Management Thought Leaders Part 91 – Frank Leistner

The late Frank Leistner was the former Chief Knowledge Officer for SAS Global Professional Services, where he founded the knowledge management program and led a wide range of knowledge management initiatives up until 2012.

Leave a Comment

Comments are reviewed and must adhere to our comments policy.

0 Comments