Lucidea’s Lens: Knowledge Management Thought Leaders

Part 101 – Larry Prusak

Stan Garfield

The late Larry Prusak was a researcher, consultant, author, speaker, and teacher. Larry was much beloved by those who met him, collaborated with him, and learned from him. His passing in 2023 was a great loss to the field of knowledge management, but his wisdom and our fond memories of him live on. He had one of the great minds in the field, providing useful insights based on his extensive reading, keen observations, and deep thinking.

The late Larry Prusak was a researcher, consultant, author, speaker, and teacher. Larry was much beloved by those who met him, collaborated with him, and learned from him. His passing in 2023 was a great loss to the field of knowledge management, but his wisdom and our fond memories of him live on. He had one of the great minds in the field, providing useful insights based on his extensive reading, keen observations, and deep thinking.

Larry was Founder and Executive Director of IBM’s Institute for Knowledge Management (IKM) and Principal and Founder of Ernst & Young’s Center for Business Innovation, specializing in issues of corporate knowledge management. He co-directed (with Tom Davenport) the Working Knowledge Research Center program at Babson College, where he was a Distinguished Scholar in Residence.

Here are definitions for five of Larry’s specialties:

- Culture: The way things are done in an organization, and what things are considered to be important and taboo

- Idea Generation: The creative process of generating, developing, and communicating new ideas, where an idea is understood as a basic element of thought that can be either visual, concrete, or abstract.

- Learning: The act of gaining knowledge from others, from existing information, and by doing

- Sharing: Allowing someone else to use something that you have–what you have learned, created, or proved–so that others can learn from your experience and reuse what you have already done.

- Storytelling: Using narrative to ignite action, implement new ideas, communicate who you are, build your brand, instill organizational values, foster collaboration to get things done, share knowledge, neutralize gossip and rumor, and lead people into the future.

Larry created the following content. I have curated it to represent his contributions to the field.

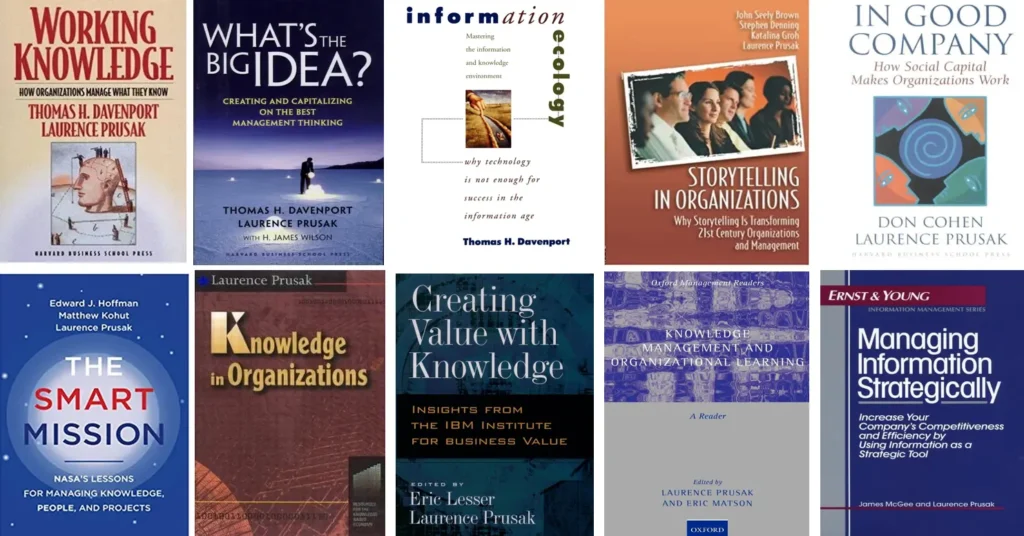

Books

The World is Round

Their mistake is that they’re confusing information with knowledge. This isn’t a new idea. College professors have forever struggled with students’ efforts to pass off the former as the latter. But consultants, journalists, and businesspeople have dangerously blurred the distinction as they’ve championed trillions of dollars’ worth of IT purchases made with the intention of “managing knowledge.” For the most part, what we’ve built is a vast global IT infrastructure that is very good at moving information, but not knowledge, from one place to another.

What’s the difference between information and knowledge? Information is a message, one-dimensional and bounded by its form: a document, an image, a speech, a genome, a recipe, a symphony score. You can package it and instantly distribute it to anyone, anywhere. Google, of course, is currently the ultimate information machine, providing instantaneous access to virtually any piece of information you can imagine—including instructions for how to perform a laparoscopic appendectomy. But I’ll wager no one would opt to have an appendectomy performed by that young woman in Shanghai—no matter how much information she’d gathered on the procedure—unless she’d also had years of hands-on surgical training. Only those years of reading, watching, and doing, under a skilled tutor’s watchful eye, would give her the knowledge to expertly perform the surgery.

Knowledge results from the assimilation and connecting of information through experience, most often through apprenticeship or mentoring. As a result, it becomes embedded in organizations in ways that, so far, have largely evaded codification. Knowledge gives firms the ability to create new drugs, design racing boats, offer useful competitive advice, and so on. And while the cost of obtaining, storing, and moving information has plummeted, the cost of doing so with knowledge hasn’t dropped much at all (in the case of surgical training and some other skills, it has probably increased). That’s because no amount of IT can—at least not yet—crack the problem of how to speed knowledge acquisition. It takes about the same amount of time today to learn French, calculus, or chemistry as it did 200 years ago. Knowledge is time-consuming and expensive to develop, retain, and transfer—and that’s as true for organizations and countries as it is for individuals.

Where Did Knowledge Management Come From?

The three practices that have brought the most content and energy to knowledge management are information management, the quality movement, and the human factors/human capital movement. Information management developed during the seventies and eighties and is usually understood as a subset of the larger information technology and information science world.

Information management is a body of thought and cases that focus on how information itself is managed, independent of the technologies that house and manipulate it. It deals with information issues in terms of valuation, operational techniques, governance, and incentive schemes. “Information,” in this context, generally means documents, data, and structured messages.

In broad terms, knowledge management shares information management’s user perspective – a focus on value as a function of user satisfaction rather than the efficiency of the technology that houses and delivers the information. Information technology focuses, for instance, on how many bits an electronic pipeline can carry; information management and knowledge management focus more on the quality of the content and how much it benefits the recipient and the organization for which he or she works. Information management discovered that not all information is created equal, that different types of information have different values and need to be handled differently. This insight—which is more true of knowledge —remains at the heart of knowledge management today. We see it in our ongoing discussions of what techniques and technologies are appropriate for sharing different kinds of knowledge and in our focus on knowledge use, not just knowledge availability.

The quality movement focused significantly on internal customers, overt processes, and shared, transparent goals. While knowledge management has not yet achieved the levels of measurable success that the quality movement can claim, it has usefully borrowed these three goals and adapted them to the somewhat different aims of knowledge management. Quality techniques were applied most successfully to manufacturing processes, while knowledge management has a broader scope, including processes that do not seem to lend themselves readily to measurement or even clear definition. Yet much knowledge work involves making knowledge visible and therefore developing knowledge processes, process owners, and governance structures in ways that owe a significant debt to the techniques of analysis and improvement developed by the quality movement.

The human capital approach has a strong and well-known theoretical base. In practice, though, our understanding of the value of human capital (and the importance of investing in it) tends to get distorted or diluted. The essential message from investigators of human capital is the financial advantage to states and firms of investing in individuals, mainly through education and training. This kind of investment has a higher return rate (in the form of higher worker productivity, skills development, innovative capacity, and ease of labor mobility) than many or all other options. Yet many organizations continue to think of their employees and their education programs as expenses rather than investments.

Ideas about human capital and how it can be developed to increase innovation and productivity are still in the early stages of being established in firms. By definition, human capital focuses on the individual, whereas most knowledge management work is concerned with groups, communities, and networks. Nevertheless, knowledge management builds on human capital ideas and has, as one of its tasks, to continue making the value of human capital clear to organizational leaders while developing tools and techniques for investing and reaping benefits from it. However, it is becoming more concerned with group knowledge and the processes of social capital that undergird group knowledge.

The One Thing That Makes Collaboration Work

If I had to pick the one thing to get right about any collaborative effort, I would choose trust. Yes, trust. More than incentives, technology, roles, missions, or structures, it is trust that makes collaboration really work. There can be collaboration without it, but it won’t be very productive or sustainable in the long run.

You might rush to agree, but first consider that what a leader needs to do to generate trust in an organization:

- Promote trustworthy people

- Work with your own employees

- Publicize the costs of distrust

- Give people a reason beyond their pay to come to work

- Reduce pay inequality

The first is the most important: it’s the strongest signal by far you can send employees about the values you actually live by (rather than those you just talk about). And it looks like a no-brainer. Who doesn’t promote trustworthy people?

Yet trustworthiness is pretty low on the scale of reasons for promotion in most firms. To pick just a few attributes (in no particular order), it ranks far behind sales records, skills, hard work, intense focus on one’s advancement, the right background and social connections, acumen at office politics. Do you think Dick Fuld was really trusted at Lehman Brothers or Chuck Prince at Citicorp?

That second one looks simple enough, too. But it becomes more complicated when I suggest that by “your own employees” I mean not just your direct reports but people further down the hierarchy, and when I say “work with” I mean closely, physically, and socially. What I’m really talking about is a judgment about time priorities, which is far from simple.

As to toting up costs for number 3, that is fairly simple. Distrust raises transaction costs higher than they might otherwise be, causing real dollar-and-cents losses. Without trust, a company needs a plethora of lawyers, managers, and accountants watching and recording and negotiating. The absence of trust dampens the natural ease of human activities. Without trust, it’s spectacularly difficult for collaboration to flourish, even between peers and within practices. But while the costs may be clear, the day-to-day effects of absent trust aren’t obvious, and making them explicit takes effort.

And once we get down to numbers 4 and 5, we’re talking about obvious commitment and some risk. What I mean by giving people a reason to come to work beyond their pay is embodying your strategic vision in a common narrative that everyone can believe in. This may be a bit of an oblique way to establish trust, but it works. I have seen such narratives cut through all sorts of distrust at Novartis, the World Bank, the Gates Foundation, the United Nations, even the CIA. Not all the time, admittedly, but it does work. And once we start talking about reducing pay disparities, we’ve moved to ground that is neither simple nor straightforward. Still, it’s hard to establish trust between people supposedly working for a common good when one party is paid 400 times more than the other.

Trust (like distrust) is contagious. It is carried socially and can flourish when enough people in a given population display their trustworthiness. Trust is the new gold. Equally valuable, but for too many companies and too many leaders not nearly so obviously worth the effort.

Stan Garfield

Dive into Stan’s blog posts for advice and insights drawn from his many years as a KM practitioner. You can also download a free copy of his book, Profiles in Knowledge: 120 Thought Leaders in Knowledge Management from Lucidea Press, and its precursor, Lucidea’s Lens: Special Librarians & Information Specialists; The Five Cs of KM. Learn about Lucidea’s Presto, SydneyDigital, and GeniePlus software with unrivaled KM capabilities that enable successful knowledge curation and sharing.

**Disclaimer: Any in-line promotional text does not imply Lucidea product endorsement by the author of this post.

Never miss another post. Subscribe today!

Similar Posts

Lucidea’s Lens: Knowledge Management Thought Leaders Part 106 – Hubert Saint-Onge

As the creator of the Knowledge Assets Framework Hubert has shaped how businesses integrate strategy leadership and knowledge sharing to drive performance.

Lucidea’s Lens: Knowledge Management Thought Leaders

Part 105 – James Robertson

James Robertson is a pioneer in intranet strategy and digital workplace design helping organizations create seamless employee experiences. As the Founder of Step Two and a respected industry voice he has shaped best practices in content management portals and digital experience design.

Lucidea’s Lens: Knowledge Management Thought Leaders

Part 104 – Vincent Ribière

Vincent Ribière advances knowledge and innovation management through AI creativity and KM. Explore his work in academia research and industry leadership.

Lucidea’s Lens: Knowledge Management Thought Leaders Part 103 – Tony Rhem

In this edition of Lucidea’s Lens: Knowledge Management Thought Leaders we highlight Dr. Tony Rhem a leading expert in AI big data information architecture and innovation. As CEO of AJ Rhem & Associates Tony has shaped the fields of knowledge management governance and emerging technologies.

Leave a Comment

Comments are reviewed and must adhere to our comments policy.

0 Comments